En-Jung a 29 year-old South Korean, is taking her PhD in French at a prestigious university in Seoul. On the surface, her life is similar to that of a student in Paris, London or New York: studies, cafés, shopping, pop music, online chatting, etc. But although Seoul is one of the most modern capitals in the world, its social rules are amongst the most rigid, built on conservative Confucian morals that have barely changed for the last 400 years.

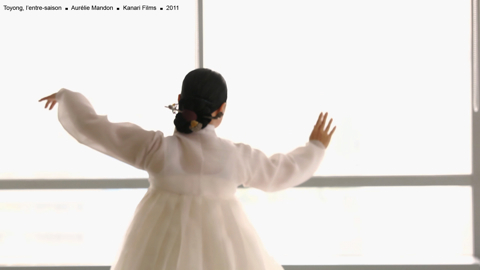

En-Jung has a boyfriend. It’s a relationship she is unable to fully enjoy because she is older, less well-off and more educated. En-Jung is a PhD student, but her mother expects her to marry and have a family. En-Jung likes to laugh, share ideas and wear tracksuits. Tradition dictates that she keeps quiet, remains unobtrusive and dresses with style. En-Jung knows France, having lived there for 2 years. She appreciates the liberty the women there enjoy. But today she lives in Seoul and she conforms, most of the time, to the Korean vision of the female sex.

Through a portrait focusing on her private world, En-Jung’s story describes the profound changes taking place in a country that’s arrived very quickly on the international scene. Young women no longer want to become “ajuma” (housewives). They are demanding financial independence and are refusing to have children. Over the last ten years, the social codes have been shaken up by the younger generation, and women in particular, who have a great deal to gain from emancipation.

This documentary is also meant to be a mirror for Western women. En-Jung is my friend and the film is constructed as a dialogue between two women who are observing one another, set against a backdrop of feminism and liberty.